There shall be allowed as a deduction expenses paid during the taxable year by a taxpayer who is a woman or widower, or is a husband whose wife is incapacitated or is institutionalized, for the care of one or more dependents (as defined in subsection (d)(1)), but only if such care is for the purpose of enabling the taxpayer to be gainfully employed…

-IRS Code Section 214 (1968)

In 1970, an unmarried man in Denver, Colorado named Charles Moritz filed for a tax deduction to hire a nurse to help him care for his aging mother.

This may sound like a mundane slice of life for a family caregiver, trying to make ends meet and provide the care his loved one needs. But Charles Moritz was denied his tax deduction because the law at the time did not recognize him as a caregiver. Section 214 of the Internal Revenue Code specifically limited the deduction to “a woman, a widower or divorcée, or a husband whose wife is incapacitated or institutionalized.” This seemingly low stakes case (Moritz’s deduction amounted to just over $300) became a career defining moment for Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 1970, when she chose to represent Moritz in the court of appeals. As the central plot for On the Basis of Sex, a major motion picture which came out early this year, Bader Ginsburg argued and won this case, stating that any law which discriminates on the basis of sex is unjust.

However, Moritz’s specific struggle struck a chord for us. As the primary caregiver for his wheelchair-bound mother, Charles Moritz’s story of obstacles and hindrances where there should have been supports, is all too familiar, even in 2019. In On the Basis of Sex, Bader Ginsburg visits Moritz in his Colorado home to convince him to appeal. He takes the meeting with this New York lawyer while keeping one ear and one eye on his mother. While Mrs. Moritz asks about her crossword and expresses some curiosity about their strange guest, her son goes on with his caregiving duties and chats about a denied tax deduction — a casual juggling act which most caregivers will immediately recognize. There are the needs of your loved one, the logistics of making it all happen, and last of all, your own needs. And yet the systems we have in place, which ought to ease this burden, often simply add one more thing to juggle.

In the end, the deduction of Section 214 was repealed by Congress’ Tax Reform Act of 1976 and replaced with Code Section 21, a slightly more generous, and certainly more inclusive credit. We now have an iteration of this same tax deduction in the Child and Dependent Tax Credit.

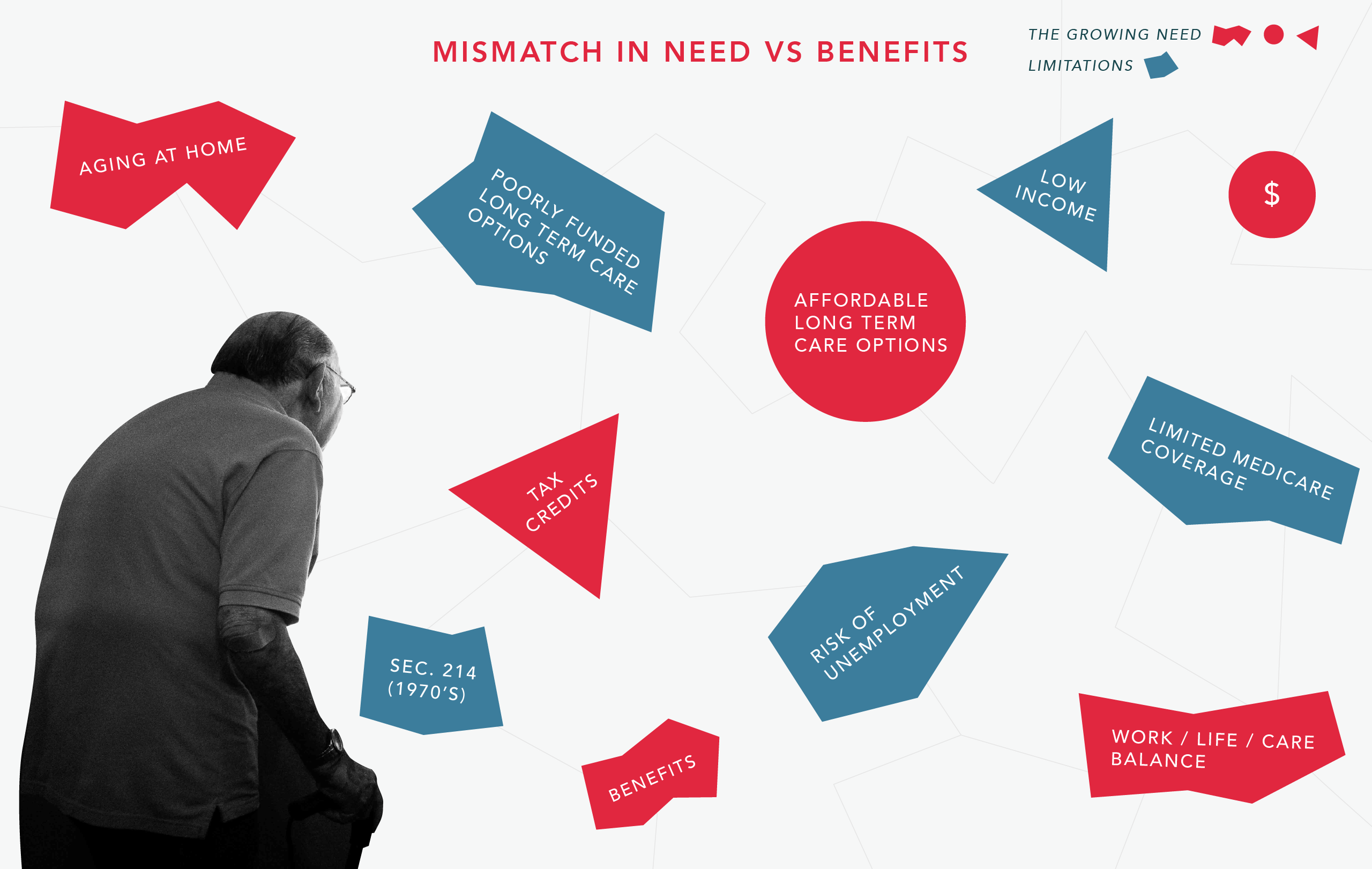

This type of piecemeal, incremental change has been par for the course too long. We identify what is missing, and slowly bandage the deficiency, cross our fingers and hope for the best. But the mismatch continues.

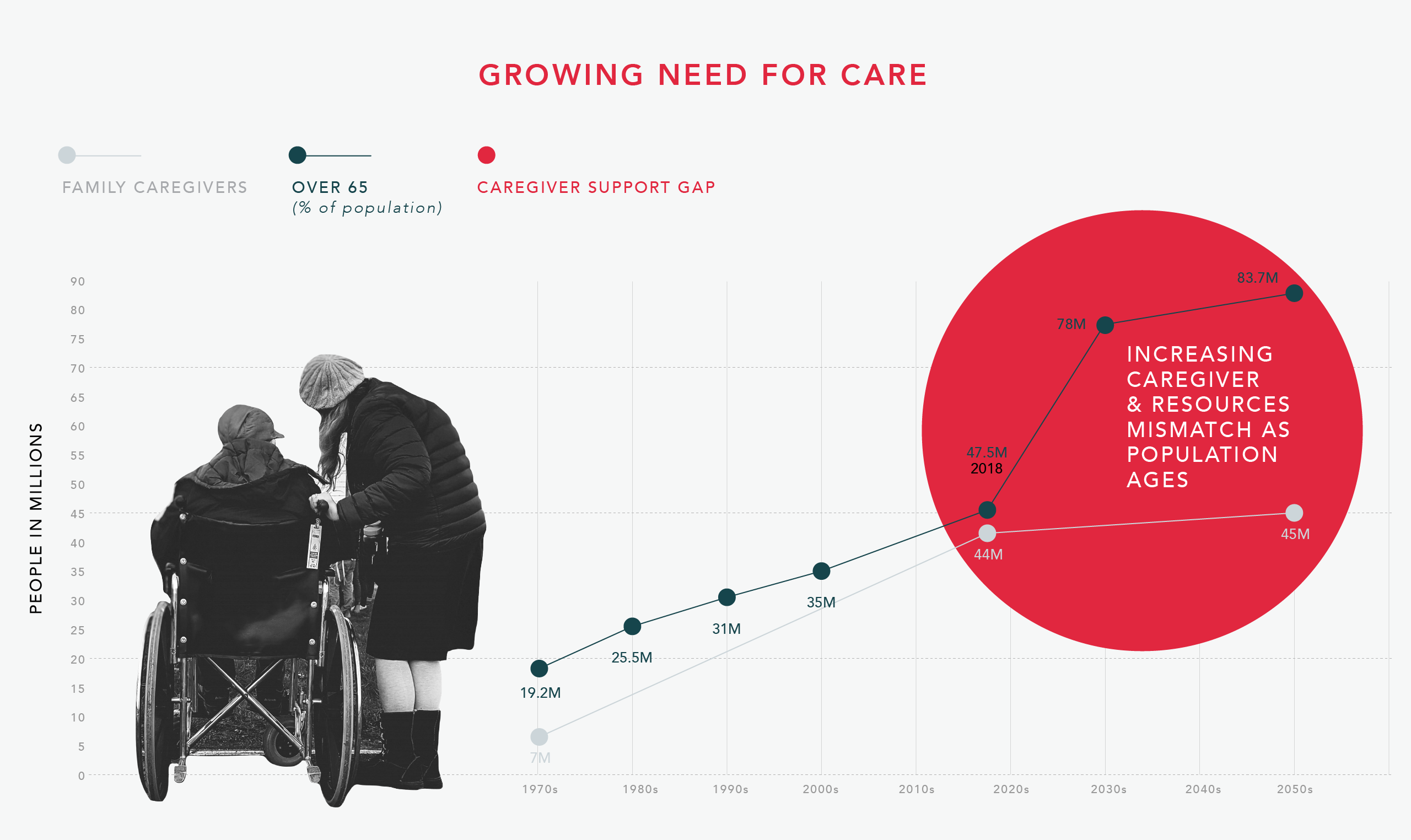

Today, as in 1970, there is an undeniable mismatch between access to the care we need, and what has been available to us — and it is only getting worse. There are currently over 40 million family caregivers in the United States, up from an estimated 7 million in 1987. As of 2017, 15% of the population is over 65 and this number is expected to grow to 24% by 2050. More and more families will require real solutions to the challenges of providing care. American families are asking how can we afford it, how can we continue to work outside the home, and how can we ensure the people we love are able to age with dignity?

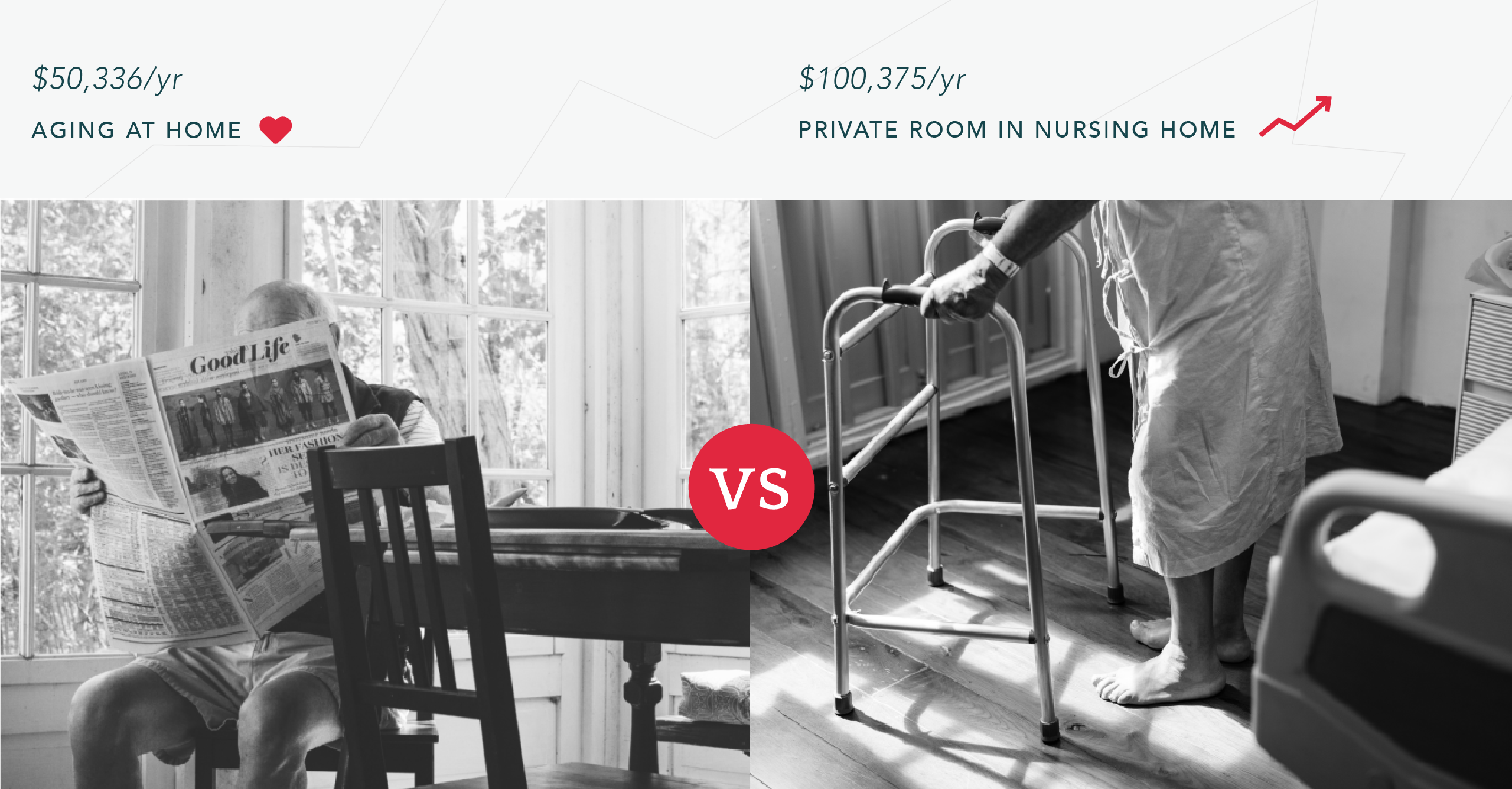

We have Medicaid and Medicare, two essential programs intended to answer these questions, yet Medicare does not cover long-term care unless it’s medical care. This means while Medicare will cover recovery from an illness or surgery, the assistance many of us will need with daily activities is not covered. If you’re eligible for Medicaid, you may be able to get long-term care through these benefits. But even though nursing home care is twice as expensive as care at home, and most seniors say they would prefer to age at home, Medicaid long-term care dollars are overwhelmingly spent on nursing homes. Between confusing exemption programs, long waiting lists for poorly funded long-term care, and the simple fact that juggling one more fight to get the care you want feels unfeasible — many Medicaid beneficiaries end up moving into institutionalized care.

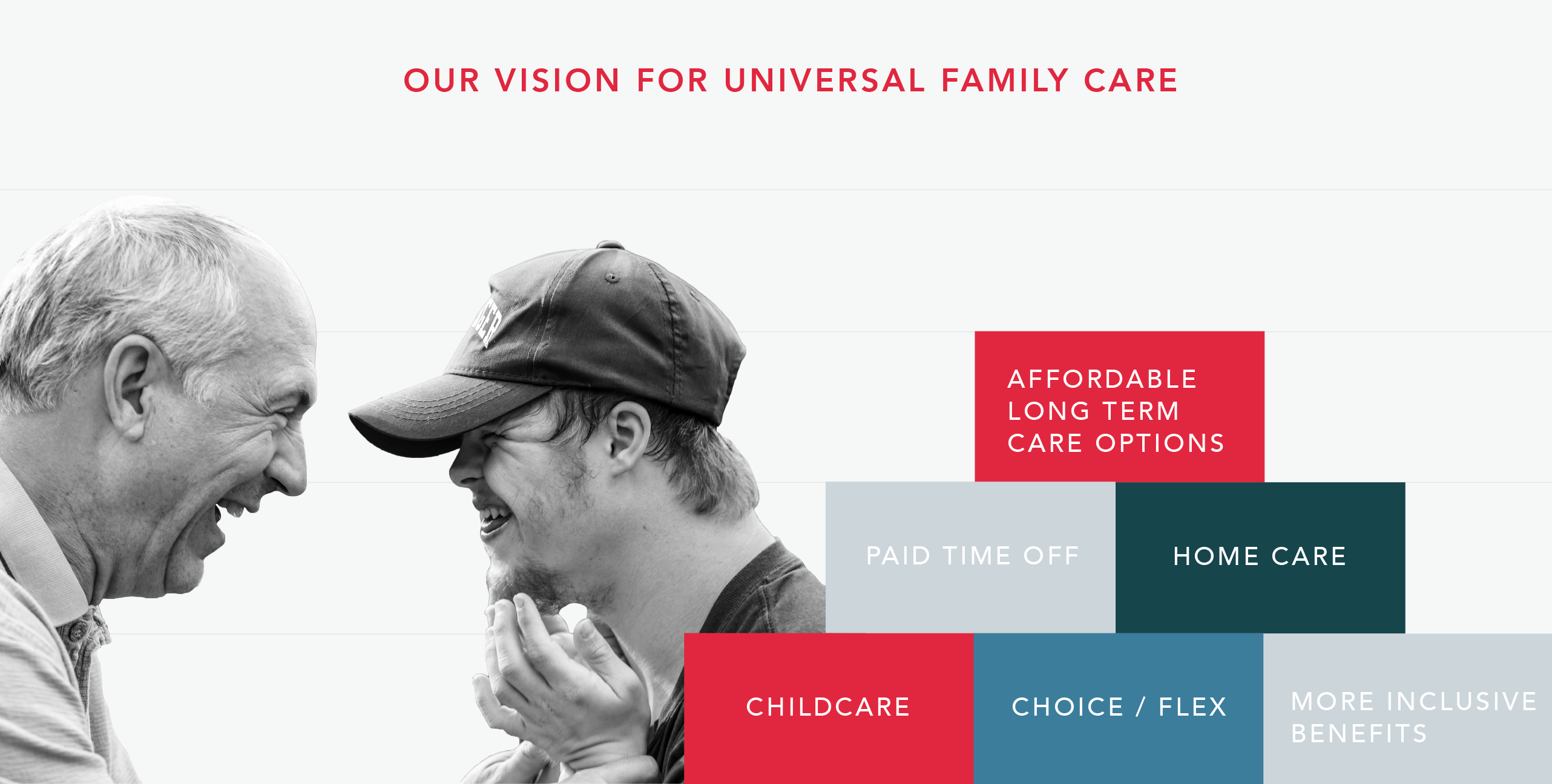

We need a universal solution. We need to prioritize the lives of family caregivers, care recipients, and care providers. This means taking a long, hard look at the benefits and solutions of the past and understanding their shortcomings. It also means taking stock of today’s dizzying array of benefits, limitations, and available credits, and realizing we can do better still.

The Child and Dependent Tax Credit, Medicare, and Medicaid are all important, much needed programs. But they aren’t enough. The care we need includes all of the stages and complexities of the lives we live and the future we want to build. This means access to and autonomy to choose quality care through all stages of life.