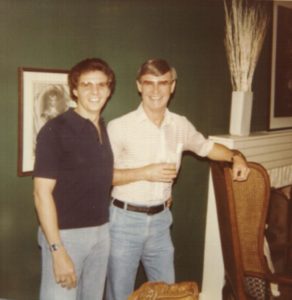

My father died in 1986. Like so many in his generation, he was lost to the AIDS pandemic. My father came out as gay in 1970, after my older brother and I had graduated high school. He and my mother divorced and he started living his best life as a gay man in Kansas City. It was there that he met Rick. Rick was the absolute love of his life and my father was Rick’s. Rick and my dad had 15 years together before AIDS took my dad from all of us.

I was close with Rick and dad, because I understood them. As my father’s only gay child, his community was my community. According to COLAGE, an organization by and for people with one or more LGBTQ parent/caregiver, I’m a second-generation Queerspawn, or a person with LGBTQ parents who is also LGBTQ.

As my father lay dying of a disease no one understood at that time, it fell to me and my brother to fight for the best care, which included fighting discrimination on the part of the VA (my father was a proud veteran) who denied my dad’s existence and would not release his records until we called a family friend who happened to be a congressman for help getting my father’s records released. End of life healthcare is hard on a family at any time but especially during a pandemic, and especially one whose transmission is not well understood.

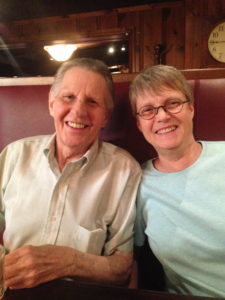

After my dad’s death, Rick did something miraculous — he lived. Rick stayed in the house he and my father lived in. He never found love again and he missed my dad fiercely until the end of his own life. As the years passed after dad’s death, we continued to look after Rick. He was, after all, our step-father, even if their relationship would not be federally recognized for decades. Though I lived in New York and my brother lived in Texas, we made sure things were comfortable for Rick in Kansas City and spoke on the phone with him a lot.

In the mid to late 2010s, Rick began to slow down. Losing not only the love of his life, but nearly his whole community, had taken its toll and between drink and smoke he was aging rapidly. From 2016-2018, I visited Kansas City often. The financial burden of flying back and forth was not small but I loved Rick and I knew my father would never want him to be alone at the end of his life. The emotional toll was also high. Though I’ve been in therapy for many years, my dad’s short life and unfair death still makes me choke up. To lose Rick was to lose the last remnant of my dad.

When Rick died in 2018, twenty two years after the love of his life, my brother, his wife, one of their daughters, my daughter and I flew down to pack up the house. We sifted through three decades of cigarette ash, documents, belongings and photographs from the years my father and Rick shared. When the house was empty (after more than one trip), my brother and I navigated selling it and Rick’s car from our respective homes, which meant different time zones, trusting the real estate agent on the ground in Kansas City and agreeing on how to divide the money.

I recently became an organizer for a group within COLAGE for people who had or have LGBTQ parents and who were born in the 1950s-1980s, before the baby boom began in the LGBTQ community in the 90s. My family was involved in COLAGE when my daughter was a kid, and my daughter is now COLAGE’S Board Co-Chair, but this group is different.

If they didn’t lose their parents to AIDS, a lot of the group members watched their parents go through the trauma of losing their community to AIDS. For a lot of us, the recent global pandemic has brought up similar trauma. For those whose parents made it to old age, there was suddenly a new concern for their safety. My fellow group members are dealing with trying to protect their parents from homophobia or transphobia in elder care facilities and from a pandemic that has been particularly deadly for older people. A lot of us are also caring for seniors we have no blood relation to, our parents’ partners, who in some cases didn’t marry because they didn’t see the need after so many years without that right. Some members of the group have parents who came out much more recently and they are finding their way into the LGBTQ community as seniors.

Navigating caring for a parent is never easy. Add in age, a global pandemic or homo/transphobia (or all three) and it compounds the difficulties and trauma. I hope anyone navigating these issues knows that they are not alone.

—

Dr. Cheryl Morris, originally from Lexington, MO, is a chiropractor living and working in Nyack, NY and New York City. She is also a member of COLAGE, the only national organization expressly dedicated to supporting people with one or more LGBTQ+ caregivers.

COLAGE unites people with lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and/or queer parents into a network of peers and supports them as they nurture and empower each other to be skilled, self-confident, and just leaders in our collective communities.